Introduction

The GALS – Gait, Arms, Legs and Spine – screen consists of three simple questions and a brief examination developed to detect significant musculoskeletal abnormalities (1). It can also be used as a screening tool prior to a more focused examination.

(1) Doherty M, Dacre J, Dieppe P and Snaith M, 1992. The 'GALS' locomotor screen. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 51(10), pp.1165-1169.

GALS – step by step video

Watch now

Video demonstration of a step by step run through of the GALS musculoskeletal screening examination.

GALS – real time video

Watch now

Video demonstration of the GALS screening examination in real time.

Routine screening questions

Screening questions that assess the musculoskeletal system should be incorporated into the routine systemic enquiry of every patient. As discussed, the main symptoms arising from disorders of the musculoskeletal system are pain, stiffness, swelling, and associated functional problems. The screening questions we use to directly address these areas are:

| Question | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Do you have any pain, swelling or stiffness in your muscles, joints or back? | focuses on the common symptoms of a musculoskeletal problem |

| Can you dress yourself completely without any difficulty? | focuses on upper limb function |

| Can you walk up and down stairs without any difficulty? | focuses on lower limb function |

A patient who has no pain or stiffness, and no difficulty with dressing or with climbing stairs is unlikely to be suffering from any significant musculoskeletal disorder. If the patient does have pain or stiffness, or difficulty with either of these activities, then a more detailed history should be taken.

The screening examination

This examination was devised for use in routine clinical assessment and takes 1–2 minutes to perform. It involves inspecting carefully for joint swelling and abnormal posture, as well as assessing the joints for normal movement.

If an abnormality of an individual area is noted in the GALS screen, that area should be examined in more detail using the relevant regional examination routine (REMS). The GALS screen is not designed to tell you what the problem is, only that there is a problem that requires further assessment.

The sequence in which these four elements (Gait, Arms, Legs and Spine) are assessed can be varied – in practice, it is usually more convenient to complete the elements for which the patient is standing before asking the patient to lie onto the couch.

Introduction

It is important to introduce yourself, explain to the patient what you are going to do, gain verbal consent to examine, and ask the patient to let you know if you cause them any pain or discomfort at any time. In all cases it is important to make the patient feel comfortable about being examined and this extends to the clothing they wear and level of exposure.

A good musculoskeletal examination relies on patient cooperation, in order for them to relax their muscles, but also the ability to view and compare joints and muscle groups if important clinical signs are not to be missed.

Gait

- Ask the patient to walk a few steps, turn and walk back. Observe the patient’s gait for symmetry, smoothness and the ability to turn quickly.

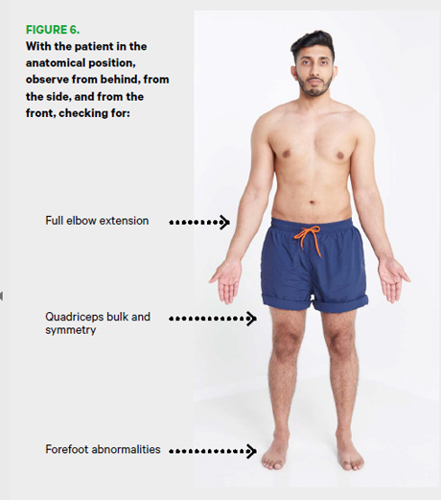

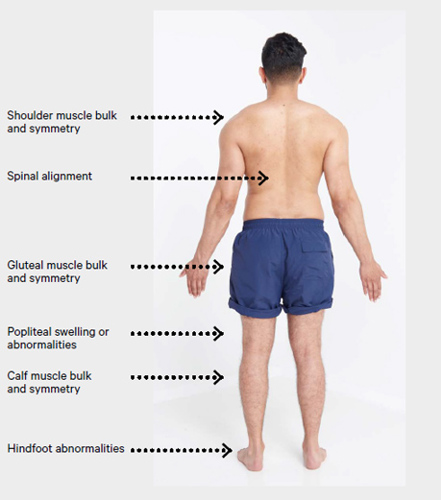

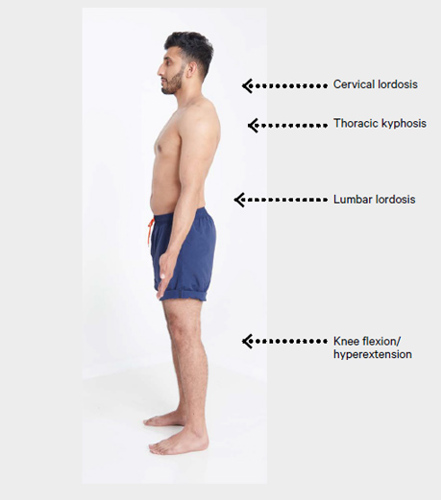

- With the patient standing in the anatomical position, observe from behind, from the side, and from in front for:

- bulk and symmetry of the shoulder, gluteal, quadriceps and calf muscles

- limb alignment

- alignment of the spine

- equal level of the iliac crests

- ability to fully extend the elbows and knees

- popliteal swelling

- abnormalities in the feet such as an excessively high or low arch profile, clawing/ retraction of the toes and/or presence of hallux valgus (see Figure 6).

Arms

- Ask the patient to put their hands behind their head. This assesses shoulder abduction (the first movement affected by rotator cuff problems) and external rotation (the first movement affected by glenohumeral problems). It also assesses elbow flexion.

- Ask the patient to straighten out their arms completely to assess full elbow extension (the first movement affected by elbow problems).

- With the patient’s hands held out, palms down, fingers outstretched, observe the backs of the hands for joint swelling and deformity. Inspect the nails and skin at the same time.

- Ask the patient to turn their hands over (the movement of supination assesses both wrist and elbow movement).

- Look at the palms for muscle bulk and for any visual signs of abnormality.

- Ask the patient to make a fist. Visually assess power grip, hand and wrist function, and range of movement in the fingers.

- Ask the patient to squeeze your fingers. Assess grip strength.

- Ask the patient to bring each finger in turn to meet the thumb. Assess fine precision pinch (which is important functionally).

- Gently squeeze across the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints (see image below) to check for tenderness suggesting inflammation within the joints. (Be sure to watch the patient’s face for non-verbal signs of discomfort.)

Legs

- With the patient lying on the couch, assess full flexion and extension of both knees, feeling over the tibiofemoral joint line for crepitus during the movements.

- With the hip and knee flexed to 90°, holding the knee and ankle to guide the movement, assess internal rotation of each hip in flexion (this is often the first movement affected by hip problems).

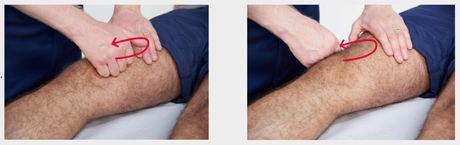

- Perform a check for a knee effusion using either a patellar tap or a sweep/bulge test:

- For a patellar tap, slide your hand down the thigh, pushing down over the suprapatellar pouch so that any effusion is forced behind the patella. When you reach the upper pole of the patella, keep your hand there and maintain pressure. Use two or three fingers of the other hand to push the patella down gently (see image below). Does it bounce and ‘tap’? This indicates the presence of a relatively large effusion.

- Small effusions may not be detected with the patella tap test and a sweep/bulge test may be useful. For a sweep/bulge test, stroke the medial side of the knee upwards (towards the suprapatellar pouch) to empty the medial compartment of fluid, then stroke the lateral side downwards (distally) (see image below). The medial side may refill and produce a bulge of fluid indicating an effusion.

- For a patellar tap, slide your hand down the thigh, pushing down over the suprapatellar pouch so that any effusion is forced behind the patella. When you reach the upper pole of the patella, keep your hand there and maintain pressure. Use two or three fingers of the other hand to push the patella down gently (see image below). Does it bounce and ‘tap’? This indicates the presence of a relatively large effusion.

- From the end of the couch, inspect the feet for localised or general swelling, deformity such as hallux valgus, clawing of the toes, and callosities on the soles which typically occur under the metatarsophalangeal joints (MTP).

- Squeeze across the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints to check for tenderness suggesting inflammatory joint disease. (Be sure to watch the patient’s face for signs of discomfort.)

Spine

- With the patient standing, inspect the spine from behind for evidence of scoliosis, and from the side for abnormal lordosis or kyphosis. Note any obvious asymmetry by looking from behind initially at the shoulders, then the pelvis, the backs of the knees and then the ankle.

- Ask the patient to tilt their head to each side, bringing the ear towards the shoulder. This assesses lateral flexion of the neck, which is sensitive in the detection of early neck problems.

- Ask the patient to bend to touch their toes. This movement is the first movement affected by lumbar spinal problems and is important functionally (for dressing). However, it can be achieved by relying on good hip flexion, so it is important to palpate for normal movement of the vertebrae. Assess lumbar spine flexion by placing two or three fingers on the lumbar vertebrae. Your fingers should move apart on flexion and back together on extension (see image below).

Recording the findings from the screening examination (GALS)

It is important to record both positive and negative findings in the notes. The presence or absence of changes – in appearance or movement – in the gait, arms, legs or spine should be recorded. For a normal result ‘GALS: NAD’ is sufficient. If there are abnormalities such as swelling or restriction of movement, these should be recorded with a brief descriptive note.

If you have been alerted to a musculoskeletal problem – by the screening questions, your examination or the spontaneous complaints of the patient – you will need to take a detailed history (as described above). You should also conduct a regional examination of relevant joints – details of how to do this can be found within The musculoskeletal examination: REMS pages.