What is Paget's disease?

Bone is a living, active tissue that’s constantly being renewed. Old and damaged bone is broken down and replaced by new healthy bone.

In Paget’s disease, the process of renewal is disrupted:

- More bone cells than usual are produced and they become larger and more active.

- The rate of bone renewal is greatly increased and is uncontrolled.

- The structure of the new bone is abnormal and weaker than usual.

- The weakened bones can bend or cause damage to nearby joints.

Blood flow is also increased, which can result in affected areas feeling unusually warm to the touch – especially if the bones are close to the surface, for example in the shins.

What are the symptoms of Paget’s disease?

Often there are no symptoms at all. Paget’s disease is often diagnosed by chance when an x-ray or blood test is taken for some other reason.

For those who do have symptoms, pain is the most common problem and is usually felt in the bone itself or in the joints near the affected bones. Pain linked to Paget’s disease may be caused by:

- increased blood flow in the affected areas, which can also result in those areas feeling unusually warm to the touch

- nerve fibres surrounding the bone being stretched as a result of bones growing larger or bending

- damage in the joints near the affected bones

- enlarged bone pressing on the nerves.

You should see your GP if you have any of the following symptoms:

- persistent bone or joint pain

- visible changes in the shape of your bones

- numbness, tingling or loss of movement – which might be signs of nerve problems.

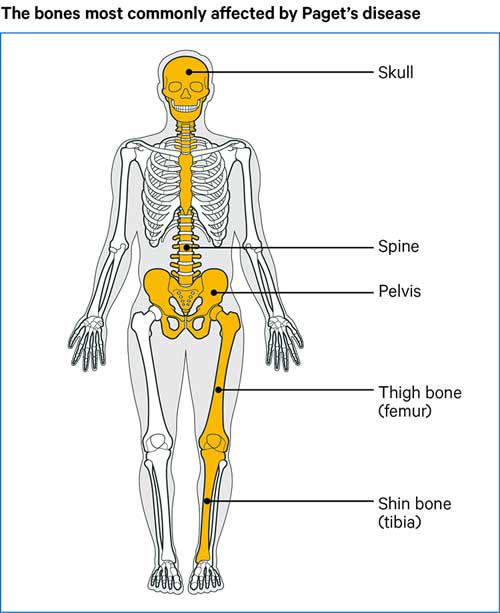

The parts of the body most likely to be affected are:

- pelvis

- spine

- legs

- skull

- shoulders.

What are the possible complications of Paget’s disease?

In time, Paget’s disease can lead to a number of other symptoms or complications that can be more serious:

Bone expansion: Bone that’s affected by Paget’s disease expands and may become deformed. Long bones may curve so, for example, one leg may end up shorter than the other.

Fractures: Bone affected by Paget’s disease is weaker than usual, so is more likely to break than healthy bone. It may also take longer than normal for a bone to heal after a fracture.

Nerve compression: When the bones expand they can sometimes squeeze nearby nerves. This is most likely in the spine, which can lead to weakness and tingling in the legs.

Deafness: If bones in the head are affected by Paget’s disease, it can result in a loss of hearing – for example if the bones around the ear become thicker.

Osteoarthritis: Abnormal bone growth can put extra strain on the joints and damage the cartilage that covers the ends of the bones. This can lead to osteoarthritis in the joint. Symptoms of osteoarthritis include pain (especially when the joint is moved), stiffness, and sometimes swelling.

Tumours: Very rarely a cancerous tumour can develop in a bone affected by Paget’s disease. It’s estimated that this happens in less than 1 in 500 cases. The first signs of this are increased pain and swelling around the tumour.

Who gets Paget’s disease?

Paget’s disease is most common in the UK. It is rare in people under the age of 50 but becomes more common with increasing age. By the age of 80, about 1 in 12 men and 1 in 20 women in the UK are likely to have Paget’s disease in some part of the skeleton.

What causes Paget’s disease?

It’s not yet known exactly what causes Paget’s disease but the genes passed on through families may play a part.

Lifestyle factors, such as poor diet, or bone injury early in life, may trigger the development of Paget’s disease in people who already have a genetic risk.

How is Paget’s disease diagnosed?

If the bone is enlarged or bent, your doctor may be able to diagnose Paget’s from your symptoms and a physical examination. They may also take into account any family history of Paget’s disease. Often, however, x-rays and blood tests are needed to confirm it.

A blood test may show a raised level of an enzyme called alkaline phosphatase. However, there are many conditions besides Paget’s disease that can cause the level of alkaline phosphatase to rise, so further tests will be needed before a definite diagnosis can be made.

Sometimes the doctor will ask for an isotope bone scan. A tiny dose of radioactive isotope is injected into a vein. Over a few hours, the isotope collects in areas of bone affected by Paget’s disease and will show up clearly when the body is scanned with a special camera. The dose of radioactive material is too small to cause any harm and quickly passes out of the body.

Once the diagnosis has been made, you may be referred to a specialist clinic for assessment and treatment.

What treatments are there for Paget’s disease?

If Paget’s disease is discovered by chance and you don’t have any symptoms, you may not need to start treatment straight away. Your doctor may suggest waiting to see if you do develop symptoms.

But sometimes doctors prefer to start treatment straight away to reduce the risk of future problems. If Paget’s disease is affecting a part of the body where complications are more likely, such as the skull, then it’s more likely that you’ll start treatment straight away.

Drugs

Paget’s disease is often treated with a group of drugs called bisphosphonates. These act mainly on the cells that break down old bone to regulate the process of bone renewal. They often help to ease any bone pain caused by Paget’s disease, although it may take a few weeks for symptoms to improve.

Types of bisphosphonates include:

| Type of bisphosphonate | How it's taken |

|---|---|

| zoledronate | Given as a single drip (infusion) but can be repeated if necessary |

| pamidronate | Series of weekly or fortnightly drips (infusions) (six in total) or sometimes as a single infusion |

| risedronate | Tablets taken daily for two months |

| tiludronate | Tablets taken daily for three months |

| etidronate | Tablets taken daily for three to six months |

Infusions of bisphosphonates are given in hospital and each one usually takes about 15–30 minutes. The advantage of infusions is that all the drug is all absorbed into the body. However, the condition can also be treated with tablets, which you may find more convenient.

If you’re taking bisphosphonate tablets:

- Take them at around the same time each day on an empty stomach.

- Avoid food for at least 30 minutes after taking your tablets, otherwise the drug won’t be absorbed into the blood stream.

- Avoid taking them within two hours either side of a calcium supplement because calcium can reduce the amount of bisphosphonate absorbed into the body.

Bisphosphonates are unlikely to cause serious side effects at the doses used for Paget’s disease. The most common side effect with pamidronate and zoledronate infusions is flu-like symptoms that last a day or two. With risedronate, tiludronate and etidronate tablets the most common side effect is a mild stomach upset.

The benefit of bisphosphonate treatment often lasts at least a year and sometimes much longer. But, if your symptoms come back, then you may need further courses of treatment with bisphosphonates.

If you can’t take bisphosphonates because of side effects, your doctor might suggest daily injections of a drug called calcitonin instead. You may be able to give these injections yourself into tissue just under the skin – a healthcare professional will show you how to do this.

If you have pain resulting from joint damage or pressure on the nerves, then you may also need painkillers such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen.

Physical therapies

It may be helpful to see a physiotherapist. For example, if one leg seems shorter than the other because the thigh and shin bones have bent, then a built-up insole in the shoe can reduce the feeling of lop-sidedness. Physiotherapists can also advise on muscle-strengthening exercise that may be useful.

An occupational therapist can offer advice on walking aids, if you need them, and aids to help with any other aspects of daily living that you may have difficulty with.

Surgery

Surgery isn’t usually needed for Paget’s disease, but can sometimes be helpful for other problems linked to Paget’s disease – for example:

- If the bone breaks then you may need an operation to fix it, depending on the type of break and how bad it is.

- If osteoarthritis develops in a joint following on from Paget’s disease, then joint replacement surgery may sometimes be needed if other treatments don’t help.

- If a bone in the back has become enlarged and is pressing on the nerves in the spine then back surgery may be needed to correct this.

How can I help myself?

It’s important that people with Paget’s disease eat a good diet with enough calcium and vitamin D. Your doctor will check whether you have a calcium or vitamin D deficiency and may suggest supplements.

Calcium

The best sources of calcium are:

- dairy products such as milk, cheese, yogurt – low-fat ones are best

- calcium-enriched varieties of milks made from soya, rice or oats

- fish that are eaten with the bones (such as sardines).

A daily intake of 1,000 milligrams (mg) of calcium should be enough, possibly with added vitamin D if you’re over 60. Skimmed and semi-skimmed milk contain more calcium than full-fat milk. If you don’t eat many dairy products or calcium-enriched substitutes, then you may need a calcium supplement. We recommend that you discuss this with your doctor or a dietitian.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is needed for the body to absorb and process calcium.

Vitamin D is sometimes called the sunshine vitamin because it’s produced by the body when the skin is exposed to sunlight. A slight lack (deficiency) of vitamin D is quite common in winter. Vitamin D can also be obtained from the diet (especially from oily fish) or from supplements such as fish oil. Oils made from the whole fish are best as fish liver oils often contain a lot of vitamin A, which can be harmful if you take too much.

If you’re worried about a lack of vitamin D, speak to your doctor about whether a vitamin D supplement would be right for you, especially if:

- you are over 60

- you don’t expose your skin to the sun very often

- you have dark skin, which reduces the amount of vitamin D you can absorb from sunlight.

Complementary medicine

There’s no research to suggest that any form of complementary medicine is helpful for Paget’s disease.

Generally speaking, complementary therapies are relatively safe if you want to try them. However, there are some risks associated with specific therapies so speak to your doctor before trying any complementary therapies.

It’s important to go to a legally registered therapist, or one who has a set ethical code and is fully insured.

If you decide to try therapies or supplements, be critical of what they’re doing for you, and base your decision to continue on whether you notice any improvement.

Research and new developments

We've funded several research projects looking into the causes and treatment of Paget's disease.

For example, researchers at the University of Aberdeen looked at how changes to proteins inside the cell can lead to disease development.

We've also funded researchers at the University of Edinburgh who have identified genes that regulate the rate at which bone is renewed, which may help explain why the disease might occur.

The Edinburgh research team are also working to develop a genetic test, which could help identify people at risk of developing the disease and those with a higher risk of complications. This information could also be used to more effectively target treatment for this condition.