What is hip replacement surgery?

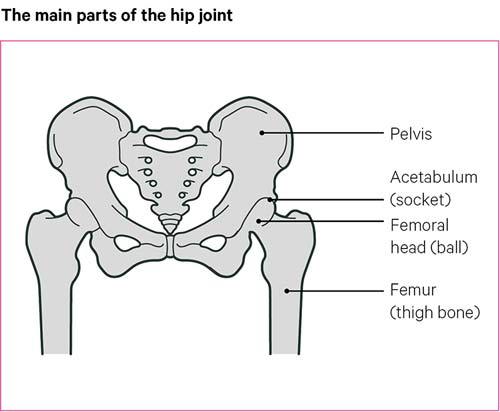

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. This type of joint allows a good range of movement in any direction.

The ball of the hip joint is known as the femoral head, and is located at the top of the thigh bone (the femur). This rotates within a hollow, or socket, in the pelvis, called the acetabulum.

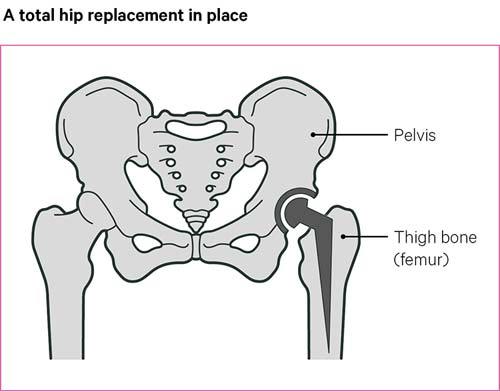

Hip replacement surgery involves removing parts of the hip joint that are causing problems – usually the ball and socket – and replacing them with new parts made from metal, plastic or ceramic.

The most common reason for having a hip replacement is osteoarthritis. Other possible reasons include rheumatoid arthritis, a hip fracture or hip dysplasia; a condition where the hip joint hasn’t developed properly.

Many thousands of people have hip replacement surgery each year. It usually brings great benefits in terms of reduced pain, improved mobility and a better quality of life.

But as with all surgery it’s important to think about the possible risks and to discuss them with your surgeon before you decide to go ahead.

Do I need surgery?

If you have arthritis in your hip your doctors will encourage you to try other options before suggesting a hip replacement. The options include painkillers, keeping to a healthy weight, exercise and physiotherapy, walking aids, or sometimes a steroid injection into the hip joint.

It may be worth thinking about surgery if pain and stiffness are having a big impact on your daily activities, or if you’re no longer able to manage your symptoms and this is affecting your quality of life.,

There are no upper or lower age limits for having hip replacement surgery. However, replacement joints do eventually wear out, so the younger you are when you have surgery, the more likely it is that you’ll need further surgery at some point in the future.

Advantages

Most people who have hip replacements notice an improvement in their overall quality of life and mobility.

Freedom from pain is often the main benefit of surgery. You should expect to have some pain from the surgery to begin with, but you’ll be given medication to help with this. Pain from the surgery itself should start to ease within the first two weeks after the operation. However, some people will have longer-term pain and, in some cases, this may need further treatment.

You can expect to have some improvement in mobility as well, although a hip replacement may not give quite as much mobility as a healthy natural hip joint. You may find it easier to move simply because there’s less pain. But you’ll probably have a greater improvement if you take an active part in your recovery – for example, by regularly doing the exercises recommended for you.

Some people find that one leg feels longer than the other after the operation. Sometimes this may be because you’ve become used to walking in a way that eases the load on your painful hip. If this is the case, physiotherapy should help. If there is a real difference in leg length, this may need to be corrected with a shoe insert or insole.

As with all major operations, there are some risks involved in the surgery itself. We’ll look at these risks in more detail later on, but your surgeon will also discuss these with you before you decide to go ahead with surgery.

Common types of surgery

There are many different types of replacement joints, sometimes called implants, that can be used in a hip replacement operation, and different ways of fixing them. Your surgeon will explain the different options and which they think will be most suitable for you.

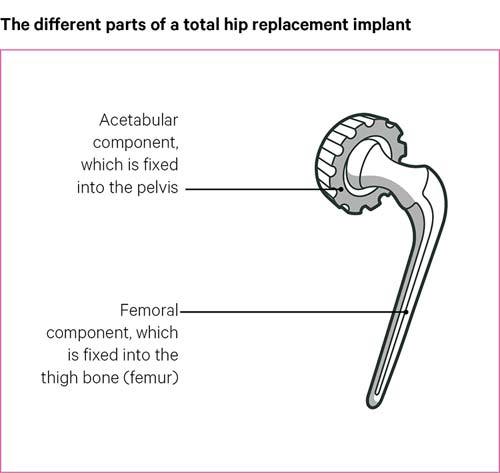

Most hip replacement operations are total hip replacements, which consist of two parts. One part is shaped like a ball on a stem and replaces the head of the thigh bone, with the stem inserted into the thigh bone. The other part is shaped like a bowl, which replaces the socket in the pelvis.

The stem of a hip replacement is always made of metal, but different combinations of metal, plastic or ceramic materials are used for the ball and the socket:

- A metal ball with a plastic socket (metal-on-plastic) is the most widely used combination.

- A ceramic ball may be used either with a plastic socket (ceramic-on-plastic) or with a ceramic socket (ceramic-on-ceramic). These combinations are often used in younger, more active patients.

The implants also come in different shapes and sizes and your surgeon will select the one that best matches your natural hip. They’ll also take into account how active you hope to be in the future. A larger diameter implant allows a greater range of movement, so may be the best option if you expect to take part in quite vigorous exercise.

Very occasionally, if ready-made implants aren’t right for you, your surgeon may have one specially made.

Often, the artificial joint components are fixed into the bone with acrylic cement, but it’s becoming more common for either one part or both parts to be inserted without cement, especially in more active patients. Where only one part is fixed with cement (usually the socket) it’s known as a hybrid hip replacement.

If cement isn’t being used, the surfaces of the implants are either roughened or else specially coated with a material made from minerals similar to those in natural bone. This provides a good surface for the bone to ‘grow onto’. Bone is an active, living tissue and, as long as it’s strong and healthy, it’ll continue to renew itself over time and provide a long-lasting bond.

Preparing for surgery

Once you’ve decided to go ahead with the operation, your name will be put on a waiting list. Your hospital will be able to tell you how long the waiting time is likely to be.

Depending on which hospital you go to, you’ll probably be asked to attend a pre-admission clinic and possibly also a ‘joint school’.

Pre-admission clinic

Most hospitals will invite you to a pre-admission clinic, usually about two to three weeks before the surgery. You’ll be examined and have tests to make sure you’re generally well enough to undergo surgery. Tests may include:

- blood tests

- x-rays of your hip

- a urine sample to rule out any infections

- an electrocardiogram (ECG) to make sure your heart is healthy.

The hospital team will probably tell you at this stage whether the operation will go ahead as planned.

You should discuss with your surgical team whether you should stop taking any of your medications or make any changes to the dosage or timings before you have surgery. It’s helpful to bring your medicines, or a list of them, along to this appointment.

Your surgeon will probably recommend muscle-strengthening exercises to do in the weeks before the operation, as this can help with your recovery.

If you smoke, your surgeon will suggest you try to stop as smoking can increase the risk of complications during and after surgery.

Joint school

Some hospitals will encourage you to attend a joint school and you may be able to bring a partner, family member or friend with you. Joint schools may vary slightly from one hospital to another but are likely to cover:

- what you should do to prepare for surgery

- what you should and shouldn’t bring with you to the hospital

- different types of implants and anaesthetics

- exercises that will be recommended after your operation

- what pain relief options you will have after surgery.

Research shows that people who take part in these classes tend to be less worried about their operation and to do better after surgery.

You’ll probably be able to speak to a physiotherapist about the exercises you’ll need to do after your operation, and to an occupational therapist, who will discuss with you how you’ll manage at home in the weeks after your operation. They’ll advise you on aids and appliances that might help.

If your hospital doesn’t run joint schools or you’re not able to attend, you should ask at the pre-admission clinic about help at home and/or useful aids.

Pre-admission checklist

Before you’re due to go into hospital, you should think about the following:

- Have you had a dental check-up lately? If not, it’s a good idea to have one as bacteria from a dental problem could get into the bloodstream and cause an infection. Loose teeth could also be dangerous if you need a breathing tube, so the surgical team may check your mouth before going ahead with the operation.

- Is there someone who can take you to and from the hospital?

- Do you need someone to stay with you for a while after your operation?

- Have you set up your home ready for your return, with everything you need within easy reach and anything that could get in your way moved?

- Think about where you’ll eat your meals. It can be difficult to carry things if you’re using crutches or walking sticks. A stool or high chair in the kitchen may be useful.

- Have arrangements been made for any special equipment you’ll need when you leave hospital – such as a raised toilet seat, bed rails or a bathroom chair? You should discuss your needs with the hospital team and check if there’s anything you’ll need to arrange for yourself.

- Have you stocked up with essential items such as groceries and toiletries? Stocking up the freezer is a good idea but think about how you will get any fresh groceries you need during the first few weeks.

Related information

-

Metal-on-metal hip replacement Q and A

Read our professional advice based on common questions about metal-on-metal hip replacement surgery, including concerns with debris from erosion in the body.

-

Your questions on surgery and arthritis

Read our professional answers to your questions about surgery and arthritis, including hip and knee replacements, enthesopathy and meniscectomy procedures.

Going into hospital

You’ll probably be admitted to hospital early on the day of surgery, though it may be earlier if you haven’t attended a pre-admission clinic or if you have another medical condition that may need attention before you can have the surgery.

You’ll be asked to sign a consent form, unless you’ve already done this at an earlier appointment, that gives your surgeon permission to carry out the treatment. You may also be asked if you’re happy for details of your operation to be entered in the National Joint Registry (NJR) database. This collects data on joint replacement operations in order to check how well different joint implants perform over a period of time.

If you’re feeling worried, you may be given a sedative (a pre-med) while you’re waiting in the admission ward. This will make you feel a little drowsy.

Just before your operation you’ll be taken from the admission ward to the operating theatre. You’ll normally be taken to theatre in your bed, but sometimes you’ll walk there with a member of the theatre team.

You’ll then be given an anaesthetic. Most hip replacements are done under a spinal anaesthetic. However, your anaesthetist will discuss the different types of anaesthetic with you and help you decide which is best for you.

Spinal anaesthetic

A spinal anaesthetic is given by a single injection into your lower back close to the spinal nerves. This begins to work straight away. You’ll be awake during the operation but will be numb from the waist down. If you’re feeling nervous about the operation, you’ll be offered a sedative along with the spinal anaesthetic, which will make you feel relaxed or sleepy.

Epidural anaesthetic

An epidural anaesthetic is also given close to the nerves in your back but through a thin plastic tube. You’ll remain awake but will be numb from the waist down. This starts to work after about 10–20 minutes. As the anaesthetic is given through a tube over a period of time, it’s useful if your operation is expected to take more than two hours.

General anaesthetic

A general anaesthetic may be given either as an injection into a vein or as a gas that you breathe in through a mask. This will send you to sleep within a minute or two. You’ll need to have a breathing tube in your throat during the operation.

If you have a spinal or general anaesthetic, you may also be given a nerve block. This is a local anaesthetic given close to the nerves that go to your leg. This can help with pain relief for some hours after the operation, but you may need to stay in bed for longer as you won’t be able to use your leg properly.

Recovery

After the operation

When you leave the operating theatre, you’ll be given any fluids and drugs you need through a tube and a needle in your arm, sometimes called a drip. You may also have plastic tubes in your hip to drain away any fluid produced as your body heals.

You’ll be taken to a recovery room or a high-care unit until you’re fully awake and your general condition is stable. Then you’ll be taken back to a ward, which may be a different one from the admission ward, often with a pad or pillow strapped between your legs to keep them apart.

You’ll need painkillers to help reduce pain as the anaesthetic wears off. These may include:

- painkilling liquids or tablets to swallow

- a local anaesthetic given around the joint during the operation

- patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) – a system where you can control your own supply of painkiller going into a vein by pressing a button

- a nerve block injection or epidural.

The hospital team will try to get you walking as soon as possible, often on the same day as your operation. To begin with, you’ll be using a walking frame, followed by elbow crutches or sticks.

The drip and any drains are usually removed within 24 hours.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy

A physiotherapist will see you in hospital after the operation to help get you moving and advise you on exercises to strengthen your muscles. They’ll also help you to learn how to walk on your crutches and use stairs safely before you go home.

A physiotherapist or an occupational therapist may offer advice on how best to get in and out of a bed, a chair, the shower etc. They may also offer advice on things to avoid.

Before you leave hospital, an occupational therapist will assess your physical ability and your situation at home, and they may arrange special equipment for you, such as a raised toilet seat or gadgets to help you dress.

Going home

How soon you can go home depends on how well the wound is healing and whether you’ll be able to get about safely. Most people will be ready to leave hospital within four to eight days.

If the surgeon feels it’s right for you, they may include you in an enhanced recovery programme (ERP). The enhanced recovery programme focuses on making sure you take an active part in your own recovery. It aims to get you walking and moving within 12–18 hours and home within one to three days.

Once you’re back at home you’ll have a routine check-up, usually six to 12 weeks after the operation, to make sure your recovery is going well. You may also be offered follow-up physiotherapy if your doctors feel that this will help your recovery.

The district nurse will change your bandages and take out any stitches. If you have any problems with your wound healing, then you should tell the hospital staff straight away.

If you were told to stop taking or change the dose of any of your regular drugs before the operation, ask your healthcare team when you should restart your medication.

Looking after your new hip joint

You need to take care, especially during the first eight to 12 weeks after the operation, to avoid dislocating the hip. You may not be able to bend your leg towards your body as far as you’d like to. Your therapist will advise you about any movements that you need to take special care with. Don’t be tempted to test your new joint to see how far it will go.

However, it’s important to continue with the programme of muscle-strengthening exercises recommended by your physiotherapist.

Getting back to normal

How quickly you get back to normal depends on many different things including your age, your general health, the strength of your muscles and the condition of your other joints.

You may need to sleep on your back at first, with a pillow or support between your legs to keep them stable. You may need a walking aid for the first few weeks, but this varies from one person to another. Your surgeon or physiotherapist will be able to advise how well you’re progressing.

Driving

You can expect to drive again after about six weeks, as long as you can safely control the vehicle and do an emergency stop. It’s important to check with your insurance company whether you’re covered during your recovery, and you need to be sure that you can safely control the vehicle in all situations.

Getting in and out of a car can be difficult – your therapist may suggest sitting sideways on the seat first and then swinging both your legs around together. Some people put a plastic bag on the car seat to make it easier to swivel round.

Working

You could return to work after about six weeks if you have a job that doesn’t involve too much moving around. If you have a job that involves a lot of walking, you may need three months or more to fully recover before returning to work. If you have a very heavy manual labour job, then you may want to think about changing to lighter duties.

Sex

You’ll probably be able to have sex after about six to eight weeks. Many people find it more comfortable to lie on their back when having sex, but don’t feel awkward about asking for advice on suitable positions.

What about sport and exercise?

Regular exercise will help with your recovery. Walking is fine, and so is swimming once your wound has been checked and is healing well. Cycling is also good, though it may be difficult at first to get on and off the bike. Dancing or sports like golf or bowls that involve bending or twisting at the hip may also be difficult at first, but should be fine after about three months.

Some surgeons and therapists suggest avoiding extreme hip movements and activities with a high risk of falling, such as skiing. Others may advise against running on hard surfaces, jumping, or sports that involve sudden turns or impacts, such as squash or tennis. If in doubt, ask your surgeon or physiotherapist for advice.

Complications

Many thousands of hip replacements are carried out each year without any complications at all. However, hip replacement is a big operation and, as with all major surgery, there are some risks. The chance of complications varies according to your general health. Your surgeon will discuss the risks with you.

Most complications are fairly minor and can be successfully treated. However, it’s important to be aware of the possible complications and to report any problems straight away. Although they’re rare, some complications can be serious and you may need another operation to correct them.

Blood clots

After surgery, some people develop blood clots in the deep veins of the leg (deep vein thrombosis, or DVT), causing pain or swelling in the leg. You should seek medical advice straight away if this happens.

There are a number of ways to reduce the risk of this happening, including special stockings, pumps to exercise the feet, and drugs that are given by injection into the skin, such as heparin or fondaparinux.

Rivaroxaban, dabigatran and apixaban are tablets that can help prevent DVT. Because they’re tablets, many people find them easier to take than injections. If your surgeon prescribes these, you’ll need to take them for four to five weeks after you go home.

You may need to wear special stockings for about six weeks after the operation.

Pulmonary embolism

A blood clot can sometimes move to the lungs, leading to breathlessness and chest pains. This needs urgent treatment.

In extreme cases a pulmonary embolism can be fatal. However, it can usually be successfully treated with blood-thinning medicines and oxygen therapy.

Dislocation

Sometimes an artificial hip may dislocate. If this happens, it will need to be put back in place under anaesthetic. This will usually stabilise the hip, although you’ll probably need to do exercises to strengthen the muscles or wear a brace to keep the joint still.

If the hip keeps dislocating, you may need further surgery or a brace to make it stable. Continuing with a programme of muscle-strengthening exercise will still help to improve stability.

Infection

To reduce the risk of infection, special operating theatres are often used, which have clean air pumped through them. And most people will be given a short course of antibiotics at the time of the operation.

Despite these precautions, a deep infection can occur in about 1 in 100 cases. The infection can be treated but the new hip joint usually has to be removed until the infection clears up. A new hip replacement will then be given six to 12 weeks later.

Wear

All hip implants will wear to some extent over time, although ceramic components generally wear less than metal or plastic ones. New, harder-wearing plastics are being developed that may help to reduce this problem.

When a joint replacement starts to wear, tiny bits of metal or plastic may come away from the replacement. These are usually absorbed into the bloodstream, then filtered by the kidneys and passed out of the body in the urine.

But in some people, the particles can cause a reaction in the soft tissues around the hip that could lead to tissue damage and other health problems (although this is rare).

This was found to be a problem in particular with metal-on-metal hip implants. As a result, a number of implants were taken off the market. Most people who received these hips won’t have problems that require further surgery, but regular check-ups have been introduced to make sure any problems are picked up quickly.

If you already have a metal-on-metal hip replacement and you’re not having regular checks, then you should contact the hospital where the surgery was carried out. You should also contact them if you’re not sure what type of hip replacement you have and start to have symptoms such as pain or swelling at or near the hip joint, a limp or problems walking, or grinding or clunking noises from the joint.

Loosening

The most common reason for a hip replacement to fail is when the artificial hip loosens. This usually causes pain, and your hip may become unstable.

Loosening is most common after 10–15 years, although it could happen earlier. It’s usually linked to thinning of the bone around the implant, which makes the bone more likely to fracture.

A fracture around the implant usually needs to be fixed surgically and the implant may need to be replaced.

Bleeding and wound haematoma

A wound haematoma is when blood collects in a wound. It’s normal to have a small amount of blood leak from the wound after any surgery.

Usually this stops within a couple of days. But occasionally blood may collect under the skin, causing a swelling.

This blood may go by itself, causing a larger, but temporary, leakage from the wound usually a week or so after surgery. But sometimes it may require a smaller second operation to remove the build-up of blood.

Drugs like aspirin and antibiotics, which reduce the risk of blood clots and infection, can sometimes increase the risk of haematoma after surgery.

How long will the new hip joint last?

Your new hip should allow you almost normal, pain-free activity for many years. Most hip replacements last for at least 15 years, although there are some differences between different brands and types of joint replacement.

Revision surgery

Repeat hip replacements (called revisions) are possible and are becoming increasingly successful. Many hospitals now have surgeons who specialise in this type of surgery.

Revision surgery is usually more complicated than the original operation, and the results may not be quite as good. If you’re having revision surgery it’s likely that you’ll be in hospital for longer than you were for the first operation, and the recovery process overall may take longer.

If it’s been some years since your first operation, it’s possible that your bone may have started to weaken. In this case you may need a bone graft, where a piece of bone is taken from another part of your body or from a donor.

Bone grafts may need to be protected from movement, and this could mean you’ll be on crutches for longer. However, the end result is usually good.

If you’re having a revision because of a deep infection, then your surgeon may suggest a two-stage revision. This involves removing the original implant and inserting a temporary spacer, usually for at least six weeks. It may still be possible to get about during this time if your other hip and leg are alright. The spacer contains antibiotics to help fight the infection. Once the infection has cleared up completely you will have the second operation to insert the new hip joint.

Research and new developments

Recent developments in hip replacement surgery include:

- minimally invasive surgery

- hip resurfacing

- bone-conserving hip replacement.

Minimally invasive surgery

Some surgeons offer a technique called minimally invasive surgery for total hip replacements. This is where the operation is carried out through a smaller incision than usual.

The smaller incision means there’s less disturbance to muscles and other tissues.

There’s some research to show that this type of surgery may result in reduced pain and better mobility in the first few weeks after surgery. However, it’s not yet clear whether there are longer-term benefits of this type of surgery.

Hip resurfacing

Hip resurfacing is an alternative type of hip replacement operation. It has the advantage that less bone is removed during the operation. It was therefore thought to be a good option for younger, more active people who would be more likely to need a further hip replacement later on.

Instead of removing the head of the thigh bone and replacing it with an artificial ball, a hollow cap is fitted over the head of the thigh bone. The socket part of the joint is replaced with a part similar to those used in total hip replacements. Both parts of the resurfacing implant are made from metal, which makes it a metal-on-metal implant.

Hip resurfacing isn’t widely used at present as it was found that metal-on-metal implants had a higher risk of wear-related complications than other types. But not everybody is at equal risk of having complications, and metal-on-metal hip resurfacing may still be an option for some people, especially larger men.

Researchers are looking into using ceramic materials for resurfacing operations, but it’s not yet known how well these will work in the longer term or if they will be a good alternative to metal-on-metal hip resurfacing.

Bone-conserving hip replacement (‘mini-hip’)

The ‘mini-hip’ is mainly available through clinical research studies, as research is still being done to find out how well they work and how long they last compared to normal hip replacements.

The replacement socket is the same as for a normal total hip replacement. However, the stem of the replacement ball is much smaller than usual. This means that the surgeon needs to remove less bone during the operation. Because less bone and other tissue is disturbed, this technique could possibly lead to quicker recovery times.

Ongoing research

Versus Arthritis is currently funding the following research:

- a collaboration jointly funded by Pfizer at Leeds University. This is developing a standard approach to follow-up care after a hip replacement that includes assessing pain and taking x-rays. This should help to identify people who are more at risk of complications so that any problems can be corrected as quickly as possible.

- a study based at the University of East Anglia, which is reviewing the UK hip implant market. It will use data from the National Joint Registry and Hospital Episode Statistics databases to explore the range and quality of products available for NHS surgeons to use.

- a study based at the University of Sheffield that aims to develop a decision aid to help people make informed choices about hip or knee replacement surgery based on their personal risk factors and National Joint Registry data on different implants and surgical techniques.

We’ve previously funded research projects which have found ways to help identify people who are more likely to need corrective surgery for complications after receiving metal-on-metal implants.

Exercises

The following exercises are suggestions to get you moving again, to strengthen your muscles and increase flexibility. Your physiotherapist may suggest others.

Start gently with just a few repeats of each exercise and gradually build up. If any of the exercises cause pain, then you should stop that exercise for a time and try it again when you feel a bit stronger. Make sure you also follow any other advice your physiotherapist gives you.

Even if you’ve only had one hip replaced it’s usually a good idea to do exercises for both legs unless you physiotherapist advises otherwise.

Lying down exercises

You can do these exercises on the bed. Repeat each exercise 10 times, and try to do them three or four times a day.

1. Glute exercise: Lie on your back. Squeeze the muscles in your bottom together, hold for five seconds and relax.

2. Quad exercise: Pull your toes and ankles towards you, while keeping your leg straight and pushing your knee firmly against the floor. Hold for five seconds and relax.

3. Heel slide: Bend your leg and slide your knee towards your chest. Slide your heel down again and straighten your knee slowly.

4. Hip abductions: Slide your leg out to the side and then back to the middle, keeping your toes and kneecap facing the ceiling.

5. Short arc quad exercise: Roll up a towel and place it under your knee. Keep the back of your thigh on the towel and straighten your knee to raise your foot off the bed. Hold for five seconds and then lower slowly.

6. External hip rotation: Lie with your knees bent and feet flat on the bed, hip-width apart. Let one knee drop towards the bed then bring it back up. Keep your back flat on the bed throughout.

7. Bridging: Lie on your back with your knees bent and feet flat on the bed. Lift your pelvis and lower back off the bed. Hold the position for five seconds and then lower down slowly.

8. Stomach exercise: Lie on your back with your knees bent. Put your hands under the small of your back and pull your belly button down towards the bed. Hold for 20 seconds.

Standing exercises

9. Hip flexion: Hold onto a work surface and march on the spot to bring your knees up towards your chest alternately. Your physiotherapist may recommend that you don’t raise your knee above hip level.

10. Hip extension: Move your leg backwards, keeping your knee straight. Try not to lean forwards. Hold onto a chair or work surface for support.

11. Heel to buttock exercise: Bend your knee to pull your heel up towards your bottom. Keep your knees in line.

12. Mini squat: Hold onto a work surface for support. Squat down until your kneecap covers your big toe.

Louise’s story

I started to have pain in the first hip when carrying heavy objects and when walking any distance.

Things became increasingly difficult and frustrating. I teach drama so I’m on my feet a lot of the time and this became challenging. I had to stop my ballroom dancing, and I found it difficult to manage my luggage when travelling to see my grandchildren.

I was diagnosed with osteoarthritis in the winter of 2014 and my first hip operation was in July 2015. The other hip was replaced in May 2018.

I had physiotherapy for six months prior to the first operation and I continued with the prescribed exercises right up to the second operation.

After the first operation I was rigorous about continuing the exercises, which I think helped me to maintain my mobility even though my other hip was becoming troublesome. When I had an x-ray before the second operation, we discovered I had no cartilage at all left in that hip.

I’m delighted with the outcome of my surgery. Overall, my recovery was as expected. I did have a couple of issues after the second operation that I didn’t have with the first, but the healthcare team have been fantastic from start to finish.

The operations have made a massive difference to my work, family and social life. Looking after the grandchildren has become much easier, and so have my teaching, housework and gardening. My husband and I can go ballroom dancing again and I can walk and cycle again too.

My advice to anybody considering a hip replacement would be to go for it!