What is Behçet's syndrome?

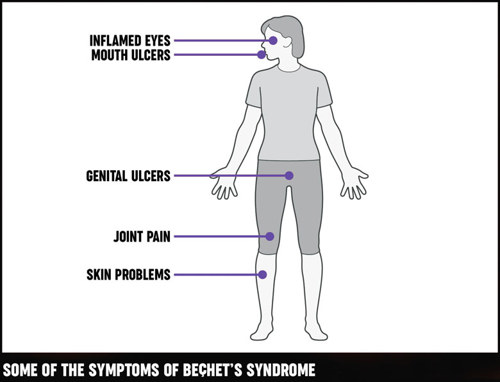

Behçet's syndrome or Behçet's disease (pronounced betchets) is a condition that causes a number of symptoms, including:

- mouth ulcers

- genital ulcers

- eye inflammation.

It's named after Professor Hulusi Behçet a Turkish skin specialist, who first suggested these symptoms might all be linked to a single disease. Since then it has become clear that the syndrome may be associated with many other symptoms.

A syndrome is a group of symptoms (what you experience) and signs (what the doctor finds by examining you). Doctors tend to talk of a syndrome rather than a disease when the cause linking the different features isn't known.

Although many doctors now refer to Behçet's disease, others believe that it may not be a single disease with a single cause. For this reason we use the term syndrome, but you'll often hear the term Behçet's disease used instead.

Who gets Behçet's disease?

Behçet's is rare in the UK, there are probably only about 2,000 people who have it. It's more common in Mediterranean countries, Turkey, the Middle East, Japan and south-east Asia. It's sometimes called the Silk Route Disease after the ancient trade routes that ran through these areas.

Behçet's syndrome can occur in most ethnic groups, and we still don't know how much ethnic background increases or reduces the chances of getting it. It affects men and women of all ages, though it's most likely to develop in your 20s or 30s. It's a long-term (chronic) condition.

Although there are families in which more than one person has Behçet's syndrome, overall most people who have this condition don't have relatives who also have it. Behçet's syndrome isn't passed directly from parent to child, but genetic factors may increase the likelihood of a person developing the condition.

Symptoms

Behçet's has a wide range of possible symptoms, but most people only have a few of these.

Mouth ulcers

About 98% of people with Behçet's syndrome have frequent mouth ulcers. They can affect the mouth, tongue and throat, and are often painful. Sometimes there are many tiny ulcers clustered together. If you only have occasional mouth ulcers, it's very unlikely that you have Behçet's. This is true even if you have a relative who has the condition.

Genital ulcers

Women and girls may get ulcers on the vulva, in the vagina or on the cervix. Men and boys may get ulcers on the scrotum and the penis. Some men and boys also have pain or swelling in the testicles. Ulcers and boils may appear around the anus and in the groin.

Neither mouth nor genital ulcers in Behçet's syndrome are caused by the herpes virus. They're not sexually transmitted or contagious, so you can't catch them from someone else.

Skin problems

Skin problems can include:

- acne-like spots

- boils

- red patches

- ulcers

- spots that look like insect-bites

- lumps under the skin.

The skin may become inflamed, ulcerated or appear to be infected.

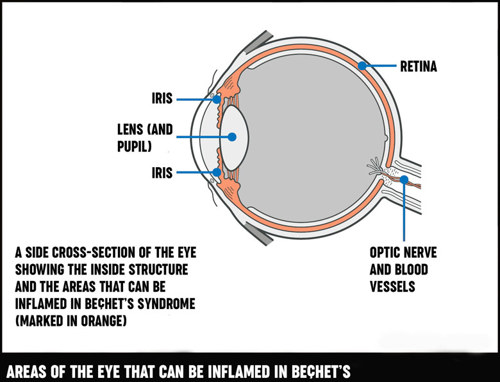

Eye inflammation

Inflammation within the eye is one of the most serious symptoms of Behçet's syndrome. The inflammation may be at the front or back of the eye, around the iris or next to the retina. It must be treated as soon as possible to avoid possible loss of sight.

If you have Behçet's syndrome and you develop new eye symptoms go straight to the emergency department of an eye hospital, or a general Accident and Emergency department.

Symptoms can include:

- floaters (dots or specks that appear to float across your field of vision)

- haziness or loss of vision

- pain

- redness in your eye.

Tiredness (fatigue)

Extreme tiredness (fatigue) is a very common symptom.

Joint problems

You may have aches, pains and swelling in various joints. These problems may come and go or they may be longer lasting. This sort of joint problem isn't the same as rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis and doesn't usually damage the joints.

Problems with the nervous system

Many people have bad headaches. These may be caused by inflammation and you may need tests, but the headaches by themselves aren't usually a sign of anything serious. The headaches often respond to the same treatments that doctors give to people with migraine.

Occasionally Behçet’s causes other symptoms such as:

- double vision

- difficulty hearing

- dizziness

- loss of balance

- fainting

- weakness or numbness in the arms or legs.

Some people with Behçet's also experience depression.

Bowel problems

Many people with Behçet's syndrome have bloating, excessive wind and abdominal pain. Behçet's sometimes causes inflammation of the bowel, leading to diarrhoea, with blood and mucus in the stools.

Blood clots (thrombosis)

Inflamed blood vessels can increase the risk of blood clots (thrombosis), but these aren't the type which cause heart attacks. Veins near the skin's surface become painful, hot and red when they're affected, and thrombosis in deeper veins leads to pain and swelling of the affected limb. The legs are affected more often than the arms. Thrombosis can occur in the blood vessels of your head, lungs or other internal organs, but this is rare.

Causes

The symptoms of Behçet's syndrome are caused by inflammation, though it's not yet clear why this happens. It's possible that a viral or bacterial infection may trigger the condition, but no specific infection has been identified. It's also possible that Behçet's may be an autoimmune disease, where the immune system attacks the body's own tissues, but this isn't yet certain.

Behçet's syndrome can't be passed on to other people. It's not associated with any other condition, a specific diet or any particular lifestyle.

How will Behçet’s syndrome affect me?

Although Behçet's syndrome is a long-term problem, it doesn't usually affect how long you live. The condition tends to go through phases when sometimes it's better than others.

Treatment may prevent new symptoms from appearing and control the existing ones. Because of the many possible problems that can occur, people with Behçet's syndrome should see a rheumatologist or another doctor with an interest in the condition.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Behçet's can take some time. There's no test to confirm the diagnosis, and the symptoms can be confused with those of other, more common illnesses. Your doctor will need to rule out other possible causes of your symptoms.

Tests

Pathergy test

You may need to take a pathergy test. This measures the increased sensitivity of the skin that occurs in Behçet's syndrome. Your doctor will give you a small pin-prick or injection, if a characteristic red spot appears on the skin around the pin-prick, then the result is positive. This doesn't mean you definitely have Behçet's, but your doctor will take this result into account, along with your symptoms, when making the diagnosis.

A definite diagnosis isn't always possible, but you might have Behçet's if you have recurrent mouth ulcers (more than three in a 12-month period) plus any two of the following:

- genital ulcers

- skin problems

- eye inflammation

- a positive pathergy test.

Blood tests

Blood tests won't confirm a diagnosis of Behçet's, but they may be taken in order to:

- rule out other diseases

- measure the degree of inflammation, for example:

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- monitor the effect of drug treatments and to check they're not causing side-effects, for example:

- full blood count

- kidney function tests

- liver function tests

- test for a genetic marker (HLA-B51), it's thought that people with this genetic marker are more likely to develop Behçet's. Its presence supports a diagnosis (although it may be found in people without Behçet's.

Parents with Behçet's syndrome sometimes ask if their children should have the HLA-B51 test to see whether they might develop the disease in the future. This isn't recommended because there's no way of knowing whether a child will develop Behçet's syndrome even if they do have this gene. If you think your child or another relative might have Behçet's syndrome, they should see their doctor and mention that there's a history of Behçet's syndrome in the family.

Additional symptoms (for example, arthritis, thrombosis) may increase the likelihood that the diagnosis is correct.

Other tests

Different people may need different tests, for example:

- You may have a chest x-ray to check there's no infection in your lungs, particularly if your doctor suggests treatment that might affect your immune system.

- If you have bowel problems you may need a telescopic examination of the bowel or stomach (endoscopy). In some specialist centres, examination of the small bowel can be carried out using a small, pill-sized camera which is swallowed (wireless capsule endoscopy).

- Computerised tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans can give more detailed images than x-rays. These scans may be needed to look further into specific symptoms.

Treatments

While there's currently no cure for Behçet's syndrome, evidence shows that there is an improved prognosis with early diagnosis and prompt treatment.

And treatment can control the severity of your symptoms and improve your general well-being.

Because Behçet's can affect many parts of the body, you may see and be treated by several different specialists. Usually one specialist will co-ordinate your treatment. This is often a rheumatologist or immunologist, who frequently works with an ophthalmologist (who specialises in eye problems).

Drugs

Many drugs can be used to control Behçet's syndrome. Doctors aim to match the strength of the drug with the seriousness of the problem since the chances of side-effects are generally higher with more powerful drugs.

There are treatments that can be applied directly to the ulcers. These include:

- mouthwashes with steroids and antibiotics

- steroid paste

- steroid sprays.

Most of these are only available on prescription. Steroids can also be prescribed to apply to the eye and to genital and skin ulcers.

Colchicine tablets are often prescribed for mouth or genital ulcers. Pentoxyfylline tablets and dapsone may also be effective.

The usual treatment for moderate to severe cases of Behçet's syndrome is a group of drugs that control inflammation by suppressing the body’s overactive immune system. Azathioprine is the most commonly prescribed but mycophenolate and ciclosporin are also used.

Some people need additional treatment with steroid tablets (usually prednisolone), although doctors try to limit the use of these because of their side-effects, particularly the increased risk of osteoporosis.

There's evidence that anti-TNF drugs, for example infliximab and adalimumab, may be effective if other treatments don't help. These have been highly successful in other inflammatory illnesses (such as rheumatoid arthritis) and are becoming more widely used in Behçet's syndrome. However, these drugs are expensive and approval for use needs to be given within the NHS on an individual patient basis.

Thalidomide can also be useful for treating severe ulceration, although doctors are cautious about giving this to women who may become pregnant. This is because of the risk of severe birth defects. It can also cause damage to nerves and its use is therefore becoming less common. Special arrangements apply for its prescription, so it's not always approved.

A drug called interferon alpha is currently being tested. It works by suppressing the immune system and may be helpful for all symptoms of Behçet's.

You may need painkillers in addition to the drugs mentioned above to ease joint pain. Over-the-counter painkillers (for example paracetamol) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (for example ibuprofen) may be enough, but your doctor may be able to prescribe something stronger if not.

Managing symptoms

Learn more about how to manage the symptoms of Behçet's syndrome.

Exercise

It's important to exercise your joints and to keep up your general level of fitness. Do as much as you can but make sure you rest when you feel you need to. Exercise such as yoga or Pilates may also help to reduce stress, which can sometimes trigger a flare-up of symptoms in some people.

Diet and nutrition

A poor diet won't cause Behçet's syndrome. But we recommend a healthy, nutritious and balanced diet, with plenty of fruit and vegetables and water, and not too many fats and sugars. This, alongside an active lifestyle, will improve your general health.

Complementary medicine

There's no evidence to suggest that any particular complementary medicine can help ease the symptoms of Behçet's syndrome. Generally speaking, though, complementary and alternative therapies are relatively well tolerated, but you should always discuss their use with your doctor before starting treatment. There are some risks associated with specific therapies.

In many cases the risks associated with complementary and alternative therapies are more to do with the therapist than the therapy. This is why it's important to go to a legally registered therapist or one who has a set ethical code and is fully insured.

If you decide to try therapies or supplements, you should be critical of what they're doing for you, and base your decision to continue on whether you notice any improvement. If your therapist suggests that you should stop your prescribed treatment, you should consider the safety of this advice very carefully and discuss it with your rheumatologist or GP.

Related information

-

Exercising with arthritis

Find out more about exercising with arthritis and what types of exercises are beneficial for certain conditions.

-

Eating well with arthritis

There’s a lot of advice about diets and supplements that can help arthritis. We explain which foods are most likely to help and how to keep to a healthy weight.

-

Complementary and alternative treatments

Learn about complementary and alternative treatments for arthritis, how they differ from conventional medicine, how they help, safety and possible risks.

Living with Behçet’s syndrome

Any long-term condition can affect your mood, emotions and confidence, and it can have an impact on your work, social life and relationships.

Talk things over with a friend, relative or your doctor if you do find your condition is getting you down. You can also contact support groups if you want to meet other people with Behçet's.

Sex and pregnancy

The genital ulcers associated with Behçet's can sometimes make sex uncomfortable or even painful. However, they're not sexually transmitted or contagious.

Some of the drugs used to treat Behçet's syndrome can affect sperm, eggs, fertility or even the baby, for example, thalidomide is known to be harmful to an unborn child. It's important to discuss your plans with your doctor if you're thinking of having a baby. This applies to both men and women with Behçet's syndrome. However, there's no reason why you shouldn't have a family, and the chances of your children inheriting the condition are tiny.