What is knee pain?

Having sore knees is common and isn’t usually a sign of anything serious. There are many possible causes, which can range from a simple muscle strain or tendonitis, to some kind of arthritis. Sometimes a cause can’t be found.

Knee pain can often be treated at home and you should start to feel better after a few days.

As you age, getting knee pain may become more common. You’re also more at risk of getting knee pain if you are overweight. Knee pain may sometimes be the result of a sports or other injury.

How is the knee structured?

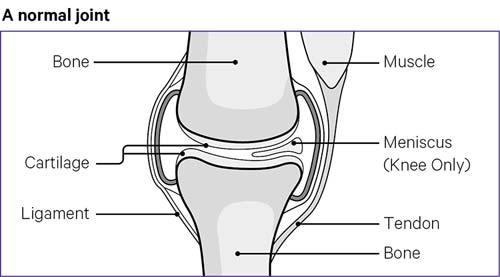

The knee is the largest joint in your body.

It is made up of four main things: bones, ligaments, cartilage and tendons.

Bones

Your knee joint is formed where three bones meet. These are your:

- thighbone, which is also known as the femur

- shinbone, which is also known as the tibia

- kneecap, which is also known as the patella.

Ligaments

These join bones to other bones. There are four main ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold your bones together and keep your knee in place.

These ligaments in your knee are:

- Collateral ligaments – which are found on the sides of your knee. One is on the inside and one is on the outside. They control the sideways movement of your knee.

- Cruciate ligaments – which are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an X shape. These ligaments control how your knee moves backwards and forwards.

Cartilage

There are two types of cartilage in your knee:

Articular cartilage

This covers the ends of your thighbone and shinbone, and the back of the kneecap. This is a slippery substance that helps your knee bones glide smoothly across each other as you bend or straighten your leg.

Meniscal cartilage (meniscus)

These are two wedge-shaped pieces that act as shock absorbers between your shinbone and thighbone.

The medial meniscus is on the inner side of the knee joint.

The lateral meniscus is on the outer side of the knee.

The meniscus helps to cushion and stabilise the joint, which is why they are tough and rubbery. When people say they have torn cartilage in the knee, they are usually talking about torn meniscus.

Tendons

These connect muscles to your bones.

Causes

Knee injuries

Sprains, strains and tears are all types of knee injury. These can be caused by sports injuries, but you don’t have to be sporty to have this type of knee pain.

Tendonitis

Sore or painful knees can be a sign of tendonitis.

This is when a tendon swells up and becomes painful - for example, after an injury. Visit the NHS website for more information on tendonitis.

Osgood-Schlatter's disease

This is a condition that can affect children and young people. In Osgood-Schlatter’s disease, the bony lump below your knee cap becomes painful and swollen during and after exercise.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

This is a common knee problem, that particularly affects children and young adults. People with patellofemoral pain syndrome usually have pain behind or around the kneecap.

Pain is usually felt when going up stairs, running, squatting, cycling, or sitting with flexed knees.

Exercise therapy is often prescribed for this condition.

Could my knee pain be arthritis?

Knee pain can develop gradually over time, might come on suddenly, or might repeatedly come and go. Whatever pattern the pain has, it is most often not due to arthritis, but might be in some people.

Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis. It can affect anyone at any age, but it is most common in people over 50.

If you have osteoarthritis of the knee, you might feel that your knee is painful and stiff at times. It might affect one knee or both.

The pain might feel worse at the end of the day, or when you move your knee, and it might improve when you rest. You might have some stiffness in the morning, but this won’t usually last more than half an hour.

Pain from osteoarthritis might be felt all around your knee, or just in a certain place, such as the front or side. It might feel worse after moving your knee in a particular way, such as going up or down stairs.

Managing symptoms

Balancing rest and exercise

During the first 24 to 48 hours after your knee problem has started, you could:

- rest your knee, but avoid having long periods where you don’t move at all

- when you are awake, move your knee gently for 10 to 20 seconds every hour.

After 48 hours:

- Try to use your leg more, as exercise can help with long-term pain.

- When going upstairs, lead with your good leg. Use the handrail, if there is one.

- When going downstairs, lead with your sore leg. Use the handrail, if there is one.

- Try to stick to your normal routine, if you can, as this can help your recovery. This includes staying at, or returning to, work.

Avoid heavy lifting until your pain has gone down and you have good range of movement in your knee.

Low-impact exercise, such as cycling and swimming, can be useful when recovering from a knee injury.

You can also try the exercises we recommend for knee pain.

Weight management

Carrying extra body weight makes it more likely that you will get joint pain in the first place. If you have joint pain already, being overweight can make it worse. Losing even a small amount of weight can make a big difference to knee pain.

The NHS has a weight loss plan that is designed to help you lose weight at a safe rate each week, by sticking to a daily calorie allowance.

Read more about the NHS weight loss plan.

Heat/ice packs

Heat

Heat is an effective and safe treatment for most aches and pains. You could use a wheat bag, heat pads, deep heat cream, hot water bottle or a heat lamp.

Gentle warmth will be enough – there is a risk of burns and scalds if the item is too hot. You should check your skin regularly, and you should try to place a towel between the item and your skin.

Heat should not be used on a new injury. Doing this might increase bleeding under the skin and could make the problem worse.

Try not to have the heated item on your skin for longer than about 20 minutes.

Ice

Many people find that ice is helpful when used to manage short-term knee pain. Ice packs can be made from ice cubes placed in a plastic bag, or wet tea towel. You could also use a bag of frozen peas, or buy a ready-made pack from a pharmacy.

Rub a small amount of any type of oil over where the ice pack is to be placed. If the skin is broken, or you have stitches, do not cover in oil. Instead, protect the area with a plastic bag, as this will stop it getting wet.

Place a cold, wet flannel over the oil. You do not need to do this if using a plastic bag.

Put your ice pack over the flannel.

Check the colour of your skin after 5 minutes. If it is bright pink or red, remove the ice pack. If it is not pink, leave it on for another 5 to 10 minutes.

Ice can be left on for 20 to 30 minutes – if it is left on for longer, there is a risk of damaging the skin. This can be repeated every 2 to 3 hours.

Suitable footwear

Examples include sensible shoes and arch supports if you have flat feet.

Painkillers

Paracetamol

If you need a painkiller, you might take paracetamol regularly, for a few days.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – tablets

These can help with pain, inflammation and swelling. There are many types and brands. Some, such as ibuprofen, don’t need a prescription. This means you can buy them over the counter, at supermarkets and pharmacies.

Other types of anti-inflammatory painkillers do need a prescription. NSAIDs carry a number of potential side effects, so you should ask your doctor or pharmacist if they are suitable for you before taking them. You can also read the patient information leaflet that comes in the packet.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – rub-on painkillers

These are also called topical painkillers. Some can be bought over the counter, at pharmacies, while others need a prescription. It is unclear whether rub-on anti-inflammatory painkillers work better than tablets. However, the amount of the medication that gets into your bloodstream is much less with rub-on painkillers, and there is less risk of side effects.

Related information

-

Let's Move with Leon

Sign up to Let’s Move with Leon our weekly email programme of 30-minute movement sessions, presented by fitness expert Leon Wormley.

-

Let's Move

Sign up to Let’s Move to receive a wide range of content about moving with arthritis – from exercise videos to stories and interviews with experts – straight to your email inbox.

When to see a doctor

Knee pain will usually go away without further medical treatment, using only a few self-help measures.

If you need help you might first see a physiotherapist or your GP.

You may be able to access a physiotherapist on the NHS without having to see your GP. You can find out if this kind of `self-referral’ is available in your area by asking at your GP surgery, local Clinical Commissioning Group, or hospital Trust.

You might also have the option of paying to see a physiotherapist privately. You don’t need a referral from a doctor to do this. You might wish to see your GP if the pain is very bad or is not settling.

See a doctor if:

- you’re in severe pain

- your painful knee is swollen

- it doesn’t get better after a few weeks

- you can't move your knee

- you can’t put any weight on your knee

- your knee locks, clicks painfully or gives way – painless clicking is not unusual and is nothing to worry about.

It’s important not to misdiagnose yourself. If you’re worried, see a doctor.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will often be able to diagnose your knee problem from your symptoms along with a physical examination of your knee. Occasionally, they may suggest tests or a scan to help confirm a diagnosis – especially if further, more specialised treatment may be needed.

Treatment

If your pain doesn’t go away, your doctor may suggest treatments to tackle the underlying cause of your knee pain. This may involve trying to make your hip muscles stronger, or help with foot problems, each of which can affect knee pain.

A doctor will suggest treatment based on the condition that’s causing your pain.

Stronger painkillers

If your pain is severe, you may be prescribed stronger painkillers such as codeine. Because this has more side effects than standard painkillers, it may only be prescribed for a short time and your doctor will probably suggest other treatments to tackle the causes of your pain.

These might include physiotherapy, talking therapies and pain management programmes, surgery or injections.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy may help your knee pain, depending on what has caused it and what part of your knee hurts. A physiotherapist can give advice tailored to your individual situation.

Treatments your physiotherapist may suggest include:

- a programme of exercises tailored to your particular needs – depending on what’s causing your knee pain, this may need to last for a while

- taping of the kneecap – this involves applying adhesive tape over the kneecap to change the way your kneecap sits or moves

- knee braces – you can buy these from sports shops, chemists and online retailers, but they’re not suitable for everyone or for all knee problems. Speak to your doctor or physiotherapist, if you want to know whether a brace is suitable for you.

Talking therapies and pain management programmes

Knee pain can affect your mood, especially if it lasts a long time, and feeling low can make your pain worse. If you’re feeling low or anxious, it’s important to talk to someone. This could be a neighbour, relative, friend, partner, doctor, or someone else in the community.

Talking therapies can also be useful for some people. You may be offered counselling on the NHS if you are struggling with long-term pain.

Counselling on the NHS usually consists of 6 to 12 sessions. You can also pay for counselling privately.

Pain management programmes can also be useful, as they help you to build on your ability to live well when you’re in pain.

ESCAPE-pain is a rehabilitation programme for people living with long-term pain that combines building upon your coping strategies, together with a tailored exercise programme for each person. The programme is delivered to small groups of people twice a week, for six weeks, and is run in many locations across the UK.

Find out if there is an ESCAPE-pain programme near you.

Surgery or injections

Surgery or injections into the knee are not recommended as a treatment for most types of knee pain. This is because people often recover as well, or better, with non-invasive treatments.

An injection is unlikely by itself to be a cure. Also, not all knee problems can benefit from injections, and injections might themselves occasionally cause side effects.

If you have osteoarthritis of the knee and it’s causing you a lot of pain and difficulty with everyday activities, then your doctor may refer you to a surgeon to discuss knee replacement surgery. You can find out more about this in our ‘Osteoarthritis of the knee’ and ‘Knee replacement surgery’ content.

Working with knee pain

If you have a job, it’s important to continue working if you can. Speak to your employer about any practical help they can offer. This might include home working, different hours, adjustments to your workplace or something else.

If you do need to take some time off, then getting back to work sooner rather than later can help your recovery.

You don’t need to wait until your knee problem has completely gone to do this.

It’s important to keep in contact with your employer and discuss what can be done to help you return to work. If your work involves heavy lifting or other physically demanding tasks, you might need to do lighter duties or fewer hours for a while.

If you have an occupational health advisor through your job, they can help suggest what work you are fit to do and arrange any simple adjustments to your work or workplace to help you stay in work.

You can ask for a workplace assessment and tell whoever carries it out about your knee pain. When working, try to take regular breaks, and have a stretch and walk around. Perhaps set a timer on your phone or computer to remind you to do this.

If you’re having any difficulties travelling to or from work, or need an item of equipment, the Government’s Access to Work Scheme might be able to help.

Research and new developments

Versus Arthritis is supporting a number of research projects in the area of knee pain, including:

- A Centre of Research Excellence in Arthritis Pain at the University of Nottingham which is investigating mechanisms of knee pain in order to find ways to better treat it in the future.

- A project based at the University of Oxford which is investigating whether it is possible to predict risk of knee pain and painful osteoarthritis following knee joint injury.

- A project based at Keele University which hopes to identify biological markers that can be used to predict which people with knee cartilage damage will respond well to cell repair therapies, and also find out why some people do not respond well to this treatment, allowing patients, doctors and surgeons to make more informed treatment decisions.

- A clinical study, based at the University of Manchester, which aims to find out whether denosumab, a drug used in the treatment of osteoporosis, can reduce the severity of knee pain and bone marrow changes in people with osteoarthritis.