What is psoriatic arthritis?

What is psoriatic arthritis video

Psoriatic arthritis (soh-rye-at-ik arth-rye-tus) can cause pain, swelling and stiffness in and around your joints.

It affects about 1 in 4 people who already have the skin condition psoriasis (soh-rye-a-sis).

Psoriasis causes patches of red, flaky skin which is covered with silvery-like patches.

Some people may develop psoriatic arthritis before the psoriasis is even present. In rare cases people have psoriatic arthritis and never have any noticeable patches of psoriasis.

Psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis are both autoimmune conditions, caused by a fault in the immune system.

Our immune system protects us from illness and infection. But in autoimmune conditions, the immune system becomes confused and attacks healthy parts of the body, often causing inflammation.

Psoriatic arthritis is a type of spondylarthritis. This is a group of conditions with some similar symptoms.

People with psoriasis are as likely as anyone else to get other types of arthritis, such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions are not linked to psoriasis.

What are the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis can cause several different symptoms around the body. People will often have two or more of these symptoms, and they can range from mild to severe.

Some of the main symptoms include:

- joint pain

- swelling in one or more joints

- joint stiffness – which feels worse when you get up after a rest and lasts longer than 30 minutes.

These symptoms are caused by inflammation inside a joint. This is known as inflammatory arthritis.

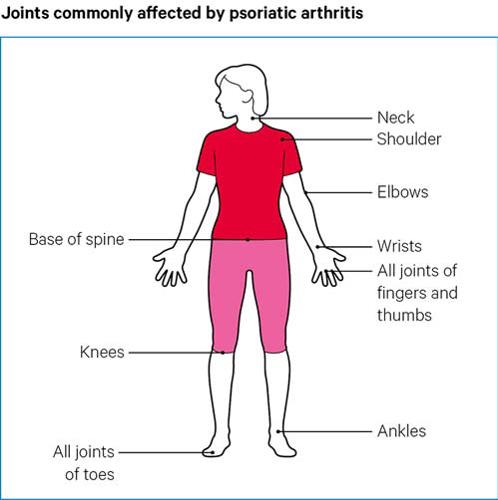

Any joint can be affected in this way. See below for the most commonly affected joints.

Psoriatic arthritis can cause pain and swelling along the bones that form the joints. This is caused by inflammation in the connective tissue, known as entheses, which attach tendons and ligaments to the bones. When they become inflamed it’s known as enthesitis.

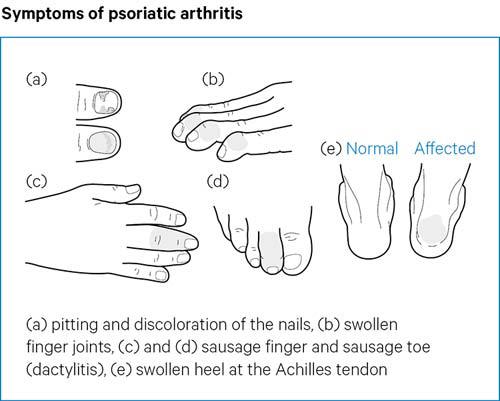

Enthesitis pain can spread over a wider area rather than just inside a joint. Affected areas can feel tender if you touch them or if there’s just a small amount of pressure on them. It commonly occurs in the feet. This can happen at the back of the heel or on the bottom of the foot near the heel. In some cases, this pain can make standing or walking difficult.

The knees, hips, elbows and chest can also be affected by enthesitis.

People with psoriatic arthritis can have swollen fingers or toes. This is known as dactylitis, or sausage digit, because it causes the whole finger or toe to swell up. It most commonly affects one or two fingers or toes at a time.

Psoriatic arthritis can also cause small round dents in fingernails and toenails, which is known as pitting. The nails can also change colour, become thicker and may lift away from your finger.

It can also cause fatigue, which is severe and persistent tiredness that doesn’t get better with rest.

What are the symptoms of psoriasis?

There are different types of psoriasis. The most common is chronic plaque psoriasis. This causes patches of red, flaky skin, with white and silvery scales.

It can occur anywhere on the skin, but most commonly at the elbows, knees, back, buttocks and scalp.

How will psoriatic arthritis affect me?

The effects of psoriatic arthritis can vary a great deal between different people. This makes it difficult to offer advice on what you should expect.

Psoriatic arthritis can cause long-term damage to joints, bones and other tissue in the body, especially if it isn’t treated.

Starting the right treatment as soon as possible will give you the best chance of keeping your arthritis under control and minimise damage to your body allowing you to lead a full and active life with psoriatic arthritis.

You don’t need to face arthritis alone. If you need support or advice, call our Helpline today on 0800 5200 520. Our advisors can give you expert information and advice about arthritis and can offer support whenever you need it most.

Complications

Having psoriatic arthritis can put you at risk of developing other conditions and complications around the body.

The chances of getting one of these are rare. But it’s worth knowing about them and talking to your doctor if you have any concerns.

Eyes

Seek urgent medical attention if one or both of your eyes are red and painful, particularly if you have a change in your vision. You could go to your GP, an eye hospital, or your local A&E department.

These symptoms could be caused by a condition called uveitis, which can cause inflammation in the middle layer of the eye.

Uveitis can permanently damage your eyesight if left untreated.

Other symptoms are:

- blurred or cloudy vision

- sensitivity to light

- not being able to see things at the side of your field of vision – known as a loss of peripheral vision

- small shapes moving across your field of vision.

These symptoms can come on suddenly, or gradually over a few days. It can affect one or both eyes. It can be treated effectively with steroids.

Heart

Psoriatic arthritis can put you at a slightly higher risk of having a heart condition. You can reduce your risk by:

- not smoking

- keeping to a healthy weight

- exercising regularly

- eating a healthy diet, that’s low in fat, sugar, and salt

- not drinking too much alcohol.

These positive lifestyle choices can help to improve your arthritis and skin symptoms.

Talk to your doctor if you have any concerns about your heart health.

Digestive System

You have an increased risk of developing Crohn’s disease if you have psoriatic arthritis. Crohn's disease is a condition in which parts of the digestive system become inflamed.

See a doctor if you have any of these symptoms, particularly if you have two or more and they don’t go away:

- blood in your poo

- diarrhoea for more than seven days

- regular pain, aches or cramps in your stomach

- fevers

- a general feeling of being unwell

- unexplained weight loss.

Liver

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a term used to describe some conditions where there is a build-up of fat in the liver. This doesn’t cause problems in the early stages. But it can lead to cirrhosis, which is when the liver becomes scarred and may stop working properly.

See a doctor if you have:

- extreme tiredness

- pain in the top right of the tummy, which can be dull or aching

- unexplained weight loss

- yellowing of the skin and eyes, which is known as jaundice

- itchy skin

- swelling in the legs, ankles, feet, or tummy.

What causes psoriatic arthritis?

The genes you inherit from your parents and grandparents can make you more likely to develop psoriatic arthritis. If you have genes that put you at risk of this condition, the following may then trigger it:

- an infection

- an accident or injury

- being overweight

- smoking.

There is also an element of chance, and it might not be possible to say for certain what caused your condition.

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are not contagious, so people can’t catch it from one another.

Diagnosis

If your GP thinks you have psoriatic arthritis, you’ll need to see a rheumatologist. These are doctors with special knowledge of the condition.

There’s no specific test to diagnose psoriatic arthritis, so a diagnosis will be made based on your symptoms and a physical examination by your doctor. Tell your doctor if you have any history of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis in your family.

If you’ve developed psoriasis in the past few years, and symptoms of arthritis have started more recently, this could suggest it’s psoriatic arthritis. But it doesn’t always follow this pattern.

It can sometimes be difficult to tell the difference between psoriatic arthritis and some other conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and gout.

Blood tests such as those for rheumatoid factor and the anti-CCP antibody can help with your diagnosis.

People with psoriatic arthritis tend not to have these antibodies in their blood. People who have rheumatoid arthritis are more likely to test positive for them – especially if they’ve had rheumatoid arthritis for a while.

These tests won’t say for certain if someone has psoriatic arthritis, but they can help when taking everything else into account.

X-rays of your back, hands and feet may help because psoriatic arthritis can affect these parts of the body in a different way to other conditions.

Other types of imaging, such as ultrasound scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may help to confirm the diagnosis.

It may take a while to get results. Check with your doctor when you are likely to get the results.

If you’re waiting for a diagnosis, there are plenty of ways you can help to manage your symptoms.

Who will be responsible for my healthcare?

You’re likely to see a team of healthcare professionals.

Your doctor, usually a rheumatologist, will be responsible for your overall care. And a specialist nurse may help monitor your condition and treatments. A skin specialist called a dermatologist may be responsible for the treatment of your psoriasis.

You may also see:

- A physiotherapist, who can advise on exercises to help maintain your mobility.

- An occupational therapist, who can help you protect your joints, for example, by using splints for the wrist or knee braces. You may be advised to change the way you do some tasks to reduce the strain on your joints.

- A podiatrist, who can assess your footcare needs and offer advice on special insoles and good supportive footwear.

Treatments for psoriatic arthritis

Because there are several features of psoriatic arthritis, there are different treatment options.

People react differently to specific treatments, so you may need to try a few options to find what works for you.

Types of treatments

For the arthritis:

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- steroid injections into joints

- disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

- biological therapies.

For the psoriasis:

- creams and ointments

- ultraviolet light therapy, also known as phototherapy

- some DMARDs and biological therapies used for arthritis can also help the psoriasis.

Treatments for the arthritis

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can reduce pain, but they might not be enough to treat symptoms of psoriatic arthritis for everyone.

Some people find that NSAIDs work well at first but become less effective after a few weeks. If this happens, it might help to try a different NSAID.

There are about 20 different NSAIDs available, including ibuprofen, etoricoxib, etodolac and naproxen.

Like all drugs, NSAIDs can have side effects. Your doctor will reduce the risk of these, by prescribing the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible period of time.

NSAIDs can sometimes cause digestive problems, such as stomach upsets, indigestion or damage to the lining of the stomach. You may also be prescribed a drug called a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), such as omeprazole or lansoprazole, to help protect the stomach.

For some people, NSAIDs can increase the risk of heart attacks or strokes. Although this increased risk is small, your doctor will be cautious about prescribing NSAIDs if there are other factors that may increase your overall risk, for example, smoking, circulation problems, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes.

Some people have found that taking NSAIDs made their psoriasis worse. Tell your doctor if this happens to you.

Steroid treatment

Steroid injections into a joint can reduce pain and swelling, but the effects do wear off after a few months.

Having too many steroid injections into the same joint can cause some damage to the surrounding area, so, your doctor will usually not recommend more than three a year.

Steroid tablets or a steroid injection into a muscle can be useful if lots of joints are painful and swollen. But there’s a risk that psoriasis can get worse when these types of steroid treatments wear off.

If used over the long term, steroid tablets can cause side effects, such as weight gain and osteoporosis. This is a condition that can weaken bones and cause them to break more easily.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

There are drugs that can slow your condition down and reduce the amount of inflammation it causes. This in turn can help prevent damage to your joints.

These are called disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Many DMARDs will treat both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Because they treat the cause of your condition rather than the symptoms, it can take several weeks or even up to three months before you feel an effect.

You’ll need to keep taking them even if they don’t seem to be working at first. It’s also important to keep taking them once they start to work. People will usually take DMARDs for many years, sometimes all their life.

The decision to use a DMARD, and which one, will depend on several factors, including what your symptoms are like and the likelihood of joint damage.

You can take NSAIDs and painkillers at the same time as DMARDs.

Like all drugs, DMARDs can have some side effects. But it’s important to remember that not treating psoriatic arthritis could lead to permanent bone and joint damage.

When taking a DMARD you’ll need regular blood tests, blood pressure checks, and in some cases a urine test. These tests allow your doctor to monitor the effects of the drug on your condition but also check for possible side effects.

There are different groups of DMARDs and they work slightly differently. DMARDs are normally taken as tablets you swallow, though methotrexate can be injected too. They reduce the activity of the immune system.

The following DMARDs can be used at early stage after diagnosis:

You may be able to try some newer DMARDs, if other treatments haven’t worked.

These newer DMARDs work on specific parts of the immune system to reduce inflammation. They’re taken as tablets you swallow.

The following can treat psoriatic arthritis:

Both drugs may be prescribed alongside methotrexate.

Biological therapies

Biological therapies are drugs that target key parts of the immune system to reduce inflammation. You might be able to try them if other drugs haven’t worked for you.

Two groups of biological therapies are used to treat psoriatic arthritis – anti-TNF drugs and interleukin inhibitors.

Anti-TNF drugs target a protein called tumour necrosis factor (TNF). Interleukin inhibitors target interleukin proteins.

The body’s immune system produces both TNF and interleukin proteins to act as messenger cells to help create inflammation.

Blocking TNF or interleukin messengers can reduce inflammation and prevent damage to the body.

A biological therapy may be prescribed on its own, or at the same time as a DMARD, such as methotrexate.

The following anti-TNF drugs can treat psoriatic arthritis:

The following interleukin inhibitors can treat psoriatic arthritis:

Biological therapies can take up to three months to fully start working.

Treatments for your skin

If your psoriasis is affecting your quality of life, or your treatment is not working, you may be referred to a dermatologist.

There are a number of treatment options for psoriasis.

Ointments, creams, and gels that can be applied to the skin include:

- ointments made from a medicine called dithranol

- steroid-based creams and lotions

- vitamin D-like ointments such as calcipotriol and tacalcitol

- vitamin A-like (retinoid) gels such as tazarotene

- salicylic acid

- tar-based ointments.

For more information about the benefits and disadvantages of any of these talk to your GP, dermatologist, or pharmacist.

If the creams and ointments don’t help, your doctor may suggest light therapy, also known as phototherapy. This involves being exposed to short spells of strong ultraviolet light in hospital.

Once this treatment has started, you’ll need to have it regularly and stick to the appointments you’ve been given, for it to be successful. This treatment is not suitable for people at high risk of skin cancer or for children. For some people, this treatment can make their psoriasis worse.

Retinoid tablets, such as acitretin, are made from substances related to vitamin A. These can be useful if your psoriasis isn’t responding to other treatments. However, they can cause dry skin and you may not be able to take them if you have diabetes.

Some DMARDs used for psoriatic arthritis will also help with psoriasis.

Surgery

People don’t often need joint surgery because of psoriatic arthritis. Very occasionally a damaged tendon may need to be repaired with surgery.

Sometimes, after many years of psoriatic arthritis, a joint that has been damaged by inflammation may need joint replacement surgery.

If your psoriasis is bad around an affected joint when you have surgery, your surgeon may recommend a course of antibiotic tablets to help prevent infection.

Sometimes psoriasis can appear along the scar left by an operation, but this can be treated in the usual way.

How can I manage my symptoms?

There are some things you can do, alongside taking prescribed medication, that may help to ease your symptoms.

Keeping active

It can be hard to keep moving if you have arthritis. Many people worry that they'll hurt themselves or further damage their joints. But the truth is staying as active as possible could actually help your symptoms.

Keeping moving will make your muscles strong, your joints mobile and help to improve symptoms such as fatigue and pain. Plus, it’s good for your mental health.

If you’re new to exercise or haven’t exercised in a while, you might feel a bit sore the first few times you try it. But, if you stick with it, it will get easier.

You don't need any special gear to get started, and a lot of physical activity can be done at home.

Start small and remember that any exercise is better than nothing. Your body is designed to move and resting too much could actually harm your joints and the tissues around them.

If you’re finding it difficult to stay motivated, it might help to exercise with a friend or in a group. It can be a great way to socialise and meet new people too.

We run activities across the country specially designed for people with arthritis, such as walking groups and Chair Chi.

See if we host any physical activity classes in your area.

If you’d rather exercise from the comfort of your own home, be sure to check out our free exercise programmes on our website. From tai chi to quick gym workouts, it’s packed full of free, online exercise classes, specially designed for people with arthritis.

Learn more about exercising with arthritis.

Diet

There aren’t any diets that can cure psoriatic arthritis.

Having a diet that is healthy, balanced, nutritious and low in fat, salt and sugar, is good for your overall health and wellbeing. This is particularly important if you have psoriatic arthritis.

Being overweight will put extra strain on your joints, such as your hips, knees and back. A healthy diet is also good for your heart health.

Eating plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables and drinking around two litres of water a day is also good for your health. Talk to your doctor, a dietitian or visit the NHS Eatwell Guide website if you need more information. The Eatwell Guide - NHS.

Learn more about eating well with arthritis.

Complementary treatments

Some people with psoriatic arthritis find complementary treatments are helpful, but you should always talk to your doctor first if you want to try them.

Complementary treatments come from a variety of cultural and historical backgrounds. They’re different to mainstream or conventional medication and therapies that you’ll get from GPs, rheumatology teams or physiotherapists.

Examples of complementary therapies include:

- acupuncture – fine needles are inserted at different points around the body to stimulate nerves and produce natural pain-relieving substances in the body known as endorphins

- The Alexander Technique – based on the principle of having improved posture and movement through a good understanding and awareness of the body. People who teach it say it releases tension in the body.

And there are alternative medicines that can be taken as pills or applied as creams. These can include fish body oil capsules, which contain fatty acids, known as omega-3, that are thought to have health benefits, including reducing inflammation. Some evidence suggests it’s much better to get these from eating fish like salmon, sardines, and mackerel, rather than taking pills.

There can be risks associated with some complementary treatments, so it’s important to go to a legally registered therapist, or one who has a set ethical code and is fully insured.

If you decide to try therapies or supplements, you should be thinking about what they’re doing for you, and base your decision to continue on whether or not you notice any improvement.

Sunshine

The right amount of sunshine can make psoriasis better, at least in the short term. However, too much sun and sunburn can make psoriasis worse.

For this reason, it’s a good idea to talk to your doctor if you’re planning to go abroad.

Smoking

Smoking can make psoriasis worse. It can also increase the likelihood of potential complications – such as heart problems.

If you smoke your doctor can give you advice and support to help you stop, or you can visit the NHS Smokefree website.

Aids and adaptations

You may be entitled to free support from your local authority to help make life around the home easier.

You could be offered aids that help with everyday tasks, as well as minor adaptations to your home, to help you get around.

This support is available only to people in England who have a physical or mental condition that means they’re unable to do basic tasks and activities, such as:

- cooking

- washing

- going to the toilet

- getting dressed

- cleaning

- working

- developing and maintaining family and social relationships.

If you can’t do two or more of the above tasks, and this has a significant impact on your well-being, you may be eligible.

This would entitle you to aids and minor adaptations up to the value of £1,000 per item. If you need an adaptation that will cost more than £1,000, you can apply for a disabled facilities grant.

For more information, visit the government website for a needs assessment.

Learn more about gadgets and equipment for your home. You can also find gadgets that have been specially designed for people with arthritis in our shop.

Related information

Living with psoriatic arthritis

Work and psoriatic arthritis

Having psoriatic arthritis may make some aspects of working life more challenging. But, if you’re on the right treatment, it’s certainly possible to continue working.

Help and support is available, and you have rights and options.

The Government scheme Access to Work is a grant that can pay for equipment to help you with activities such as answering the phone, going to meetings, and getting to and from work.

The 2010 Equality Act, and the Disability Discrimination Act in Northern Ireland makes it unlawful for employers to treat anyone with a disability less favourably than anyone else.

Psoriatic arthritis can be classed as a disability if it:

- makes daily tasks difficult

- lasts for more than 12 months.

Your employer may need to make adjustments to your working environment, so you can do your job comfortably and safely.

You might be able to change some aspects of your job or working arrangements, or train for a different role.

In order to get the support you’re entitled to, you’ll need to tell your employer about your condition. Your manager or HR department might be a good place to start.

Other available support might include:

- your workplace occupational health department, if there is one

- an occupational therapist. You could be referred to one by your GP or you could see one privately

- disability employment advisors, or other staff, at your local JobCentre Plus

- a Citizens Advice bureau – particularly if you feel you’re not getting the support you’re entitled to.

Learn more about working with arthritis.

Sex and relationships

Sex can sometimes be painful for people with psoriatic arthritis. Experimenting with different positions and communicating well with your partner will usually provide a solution.

Having psoriatic arthritis can put added strain on relationships with partners and close relatives. Support and understanding from those closest to you can be very important.

Good two-way communication and understanding can help. Encourage your partner and close relatives to learn about psoriatic arthritis. Let people know if you’re having a bad day. Family therapy sessions might help. The relationship charity Relate could be a good place to turn.

You can find out more here: Sex and arthritis – how to make it work.

Pregnancy, fertility and breastfeeding

Psoriatic arthritis won’t affect your chances of having children. But if you’re thinking of starting a family, it’s important to discuss your drug treatment with a doctor well in advance. If you become pregnant unexpectedly, talk to your rheumatology department as soon as possible.

The following treatments must be avoided when trying to start a family, during pregnancy and when breastfeeding:

- methotrexate

- leflunomide

- retinoid tablets and creams.

There’s growing evidence that some other drugs for psoriatic arthritis are safe to take during pregnancy. Your rheumatology department will be able to tell you which ones.

It will help if you try for a baby when your arthritis is under control.

It’s also important that your arthritis is kept under control as much as possible during pregnancy. A flare-up of your arthritis during pregnancy can be harmful for you and your baby.

Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis can run in families. If you have either condition, you could pass on genes that may increase your children’s risk though it’s difficult to predict.

As treatments continue to improve, people with psoriatic arthritis in years to come can expect a better outlook. If you have any questions or concerns, talk to your doctor.

Learn more about pregnancy, fertility and breastfeeding.

Emotional wellbeing

Living with psoriatic arthritis can cause pain and fatigue, but it can also take a toll on your mental health too.

You might feel sad, hopeless and lose interest in things you used to enjoy.

At times like this it’s important to let your loved ones know what you’re going through and, if your mood doesn’t improve, talk to your doctor. They can signpost you to useful services such as therapy, or they may prescribe you an antidepressant.

There are also plenty of small ways you can look after your mental wellbeing and build emotional resilience. For instance, you could:

- Practice deep breathing or mindful meditation to help reduce any anxiety you may have.

- Write your thoughts down in a diary to help you make sense of your emotions.

- Keep active – exercise can give you a boost of feel-good hormones called endorphins.

- Make time for activities that you enjoy, or which help you relax.

- Connect with friends – grab a coffee with a friend, have a phone call with a family member or join an online community.

If you need a bit of extra support, remember you’re not alone. We’re here to help you, every step of the way.

- You might find it helpful to join a Versus Arthritis support group where you can connect with like-minded people and talk about what you’re going through. See if we run a local support group in your area.

- Or you could join our Online Community where you could connect with real people who share the same everyday experiences as you.

- You can also call the Versus Arthritis Helpline for free on 0800 5200 520, where our trained advisors can lend a listening ear.

Sleep and Fatigue

It has been found that as many as 80% of people with arthritis have reported that they struggle with sleep.

Pain, discomfort and side effects of medication can make it harder for a person with arthritis to fall asleep and stay asleep throughout the night.

A change of habits around bedtime may help to improve sleep:

- Make sure your bedroom is dark, quiet and a comfortable temperature.

- Try a warm bath before bedtime to help ease pain and stiffness.

- Develop a regular routine, where you go to bed and get up at a similar time each day.

- You may like to try listening to some soothing music before going to bed.

- Some gentle exercises may help reduce muscle tension, but it’s probably best to avoid energetic exercise too close to bedtime.

- Keep a notepad by your bed – if you think of something you need to do the next day, write it down and then put it out of your mind.

- Avoid caffeine, alcohol and eating meals before you go to bed.

- If you smoke, try to stop smoking, or at least don’t smoke close to bedtime.

- Try not to sleep during the day.

- Avoid watching TV and using computers, tablets or smartphones in your bedroom.

- Don’t keep checking the time during the night.

Discover more tips to help you how to get a good night’s sleep and learn how to better manage your fatigue.

Your experiences of psoriatic arthritis

Research and new developments

Past research and achievements in this area

Research led by our Centre for Genetics and Genomics Versus Arthritis based at the University of Manchester identified genetic variants associated with psoriatic arthritis, but not with psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis.

This helped to establish psoriatic arthritis as a condition in its own right. The findings could lead to the development of drugs specifically for psoriatic arthritis.

Our TICOPA (Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis) trial looked at the benefits of early aggressive drug treatment for people with psoriatic arthritis – followed by an increase in drug dosage if initial treatment isn’t working. The trial found that patients treated this way, required fewer hospital- and community-based services, excluding rheumatology appointments, than patients receiving the standard care.

Ongoing studies

We’re funding a study at the University of the West of England looking at how to encourage and help people with psoriatic arthritis become informed about their condition, manage their symptoms, and feel able to make decisions about their treatment. Evidence shows that patients who adopt this proactive approach are more likely to be satisfied with care and have improved symptoms.

We’re also supporting research at Imperial College London investigating whether microbes found in the gut and on the skin are different in people with psoriatic arthritis. This could help scientists develop an easy diagnostic test, which could also be used to predict how severe the condition will become. This may lead to the development of new treatments.

Research we’re funding at the University of Glasgow is exploring why many people with psoriatic arthritis continue to experience persistent pain even after receiving effective treatments to reduce inflammation and other associated symptoms. The researchers are studying pain originating in the central nervous system, to see if it could play a role in contributing to pain in psoriatic arthritis, and this type of pain could respond to different treatments.

Ellen’s story

When I was told I had psoriatic arthritis, I was worried, and I wanted to just ignore it and hoped it would go away on its own. Once I realised this was not going to happen, I started taking my condition much more seriously.

This wasn’t the first time I was told I had arthritis though. At 18 months old, I was diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). I also developed uveitis when I was five years old and have been on steroids consistently.

Psoriasis was also a part of my life from a fairly young age. It was all over my knuckles, hands, and wrists which I would hide with my school jumper as I was very insecure about it. Despite this psoriatic arthritis was never mentioned to me growing up.

My arthritis went into remission when I was 16 years old, and I didn’t really think any more about it until I was 24. This is when I started losing vision in my left eye because of my uveitis and my joints started becoming very sore.

I saw a rheumatologist who was great, and he took a full history from me. This was the first time I was asked if I had a history of psoriasis and after a joint examination, he confirmed it. It was psoriatic arthritis.

I took to doing my own research after this appointment and started taking my condition more seriously. Something that really helped me was making notes in between appointments about how my arthritis was affecting me, so I wouldn’t forget it all when it came to seeing my doctor.

I was initially started on methotrexate, which worked wonders for me but unfortunately six months in my liver function test came back bad, so I had to stop taking it.

The next line of treatment for me was sulfasalazine which I had an awful reaction to, it gave me such bad headaches and I couldn’t concentrate, so I stopped that too and I was put on adalimumab.

Adalimumab is amazing for me, I take it every two weeks and I am surprised with how easy I find the injections as I am terrified of blood tests, but I think because I can’t see the needle and it doesn’t hurt that badly I am okay with it.

I found Versus Arthritis after I started posting about my conditions on YouTube and someone from the Young People and Families service reached out to me. I started volunteering for them about six years ago and it has been such a helpful experience making genuine connections with other people who have the same, or similar conditions to me.

If I could pass on one bit of advice it would be if you feel bad, you feel bad and just take a break don’t push yourself too far! I have definitely learnt that over the years!

Ian's story

I’ve suffered with psoriasis since being a teenager. I wore track-suit bottoms to play football, so people couldn’t see. And I had a constant aching, especially after exercise.

I was so embarrassed by the amount of psoriasis on my scalp I said I’d never visit a barber again. My wife cut my hair for 13 years.

When I was 40, I had a major back operation. My consultant asked how I’d know if things had improved, ‘If I can walk 100 yards,’ I said.

Although it’s an invisible condition to most, the impact on my life was considerable. Opening jars, changing the temperature of the shower and getting dressed were becoming more and more problematic. That’s without mentioning the impact on my mental health.

My wife worked at a GP surgery and noticed a patient with the same symptoms. After some internet research I went to see my GP again armed with information. He agreed it looked like psoriatic arthritis and referred me to a rheumatology department.

After scans, x-rays and blood tests I was diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis. It’s a pretty empty feeling when you realise you have something that will never go away.

Thanks to methotrexate, within a week the psoriasis on my scalp had all but gone – I celebrated by visiting the hairdressers.

But my joint problems continued, and at Christmas 2014 I was as low as I’d ever been. As I left work on Christmas Eve I looked back and, in my mind, said goodbye. I couldn’t see any way I could ever go back.

A week later I was prescribed adalimumab. Within a week I could feel a huge difference and as the days went on, I was feeling better and better. The inflammation in my joints was subsiding.

At the end of February 2015, I started Couch to 5K, it’s a 10-week programme but took me about 15 weeks. It was life changing.

I entered more races and joined a running club. This helped me immensely, lots of great people with encouragement, advice and friendship. Running has helped me lose a lot of weight, which has taken pressure off my joints. And it has really helped my mental health. I have done 17 half marathons, one full marathon, and several 10Ks and 5Ks.

You need to have people around you for support. Family and friends are important. So too are good physiotherapists, occupational therapists and rheumatology professionals. They’re not just about fix, fix, fix. They get what you’re going through, which is such a relief. It’s good to have an outlet that’s not your family, because you put a lot on your family.

Last weekend I grouted the bathroom. Three years ago, I simply couldn’t have done that.

In 2008 my goal was to walk 100 yards, almost exactly 10 years later I ran 26.2 miles. And I will do it again, at the London Marathon in 2020 for Versus Arthritis.